More efficient getting hydrogen out of water will help nanopena from cheap metals

Researchers at the University of Washington (WSU) have discovered a way to more efficiently generate hydrogen from water, which could be a critical solution to ensure a viable and large-scale clean energy production system.

Using relatively inexpensive metals such as nickel and iron, scientists have developed a very simple technology to create a large number of high-quality catalysts needed for a chemical reaction to break down water. Their method was described in the February issue of the journal Nano Energy.

Effective ways to convert and store energy are key areas for clean energy applications. The urgent need for them arises because solar and wind power plants are not able to generate energy around the clock. One of the most promising ideas for storing renewable energy is to use excess electricity to break down water into oxygen and hydrogen. In addition to many applications in the industry, the resulting hydrogen can also power cars, drones, trains and other fuel cell equipment.

However, the processes of water electrolysis were not widespread in large-scale production, as they required expensive catalysts from rare metals – most often platinum or ruthenium. There are a number of other methods of water splitting, but some require too much energy, while others use unstable catalytic materials.

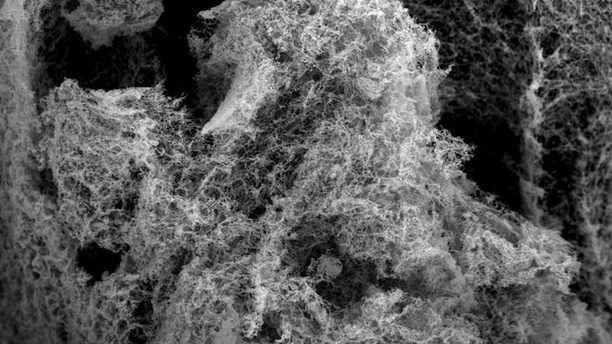

In their work, the researchers, led by Professor Yue Lin, used two affordable and cheap elements to create porous nanopena, which worked better than most of the catalysts currently used, including precious metals.

The catalyst they created turned out to look like a tiny sponge. Thanks to its unique atomic structure and many open surfaces, nanopena is able to catalyze the desired response with less energy than previously used analogues. In addition, the new material showed a very small loss of activity during the 12-hour stability test.

The WSU project was carried out in collaboration with researchers from the Argonne National Laboratory and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. After successful laboratory tests, scientists are looking for additional support for larger-scale trials.

Source ecotechnica.com.ua